Innocence Harold Brodkey A Whiter Shade Of Pale Lyrics Meaning Sketchup Make 2016 Crack 64-bit Download Complete summary of Aaron Roy Weintraub's Innocence. ENotes plot summaries cover all the significant action of Innocence. Goodreads assists you maintain track of publications you need to study. Harold brodkey innocence. Posted by Kigalabar in Best Windows Utilities apps. She said it was imposed as a measure by people who knew nothing about sex and judged women childishly. She began to chatter right away, to complain that I was still in bed; she seemed to think I'd been taking a nap and had forgotten to wake up in time to. Brodkey is murky, cloudy, discursive, brilliant, static, and often boring-in this collection, not in his First Love and Other Stories, written before he became a literary cult figure. If you've never read him, this is probably the best of his late fiction. Profane Friendship and Runaway Soul are all but unreadable.

Sea Battles on Dry Land , by Harold Brodkey. Metropolitan Books, 452 pages, $30.

Innocence Harold Brodkey Pdf

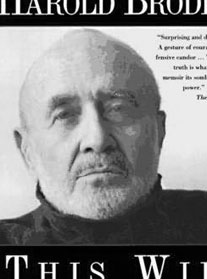

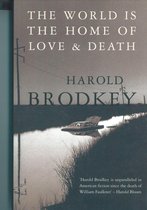

Sex and death made Harold Brodkey famous: His two best-known works are “Innocence,” the 1973 short story about a Radcliffe girl’s arduous first orgasm, and This Wild Darkness , a chronicle of his losing three-year battle with AIDS. (Brodkey died in 1996 at the age of 65.) In New York literary circles, Harold Brodkey was also famous for being Harold Brodkey. He was a man with mystique, which he frequently milked–boasting in the pages of this newspaper, for instance, of his “tremendous, pulsating, earthshaking underground reputation–as a writer, as a man, as a lover, a dinner companion, a bastard.”

But from the evidence of Sea Battles on Dry Land , an eclectic collection of Brodkey’s essays, it was New York City and literature–not eros and thanatos–that Brodkey knew best. Whatever the subject, Brodkey’s essays are wildly uneven; he ranges from fiercely incisive to laughably pretentious. If, for some reason, you consider yourself a New York intellectual, Sea Battles on Dry Land might encourage you to secede from the tribe.

Harold Brodkey Innocence Story

One of the best pieces here is also among the slightest. “The Subway at Christmas” was originally published as a “Talk of the Town” item in The New Yorker , and it is not only beautiful–with its observations of “the gloomy, heartbroken half-light in the cavern at the edge of the dry riverbed of tracks”–but trenchant, too, in its understanding of how class and social tensions emerge in the tiniest details of dress and the most insignificant gestures. Brodkey has sometimes been compared to Marcel Proust and Walt Whitman, but here he reminds me of the late Janet Flanner, The New Yorker ‘s brilliant Paris correspondent for five decades, who understood that fashions and food could tell you as much–indeed, perhaps more–about the spirit of that city than all of Charles de Gaulle’s speeches and a year’s worth of Le Monde combined.

Brodkey knew the nervous intimacy that defines New York’s public spaces. In “At Christmas,” he catalogues the “degrees of hope and kinds of style and moral and immoral intention” of his fellow travelers underground, not to mention their very cool hair: “full and bushy, strict and skimpy, waves, curls, fluff, and dreadlocks, pompadours, bangs, straightforward falls, braided falls.” He pauses to praise famous men: One beggar, he notes, is “terrifying in the sorrow of all that he had been excluded from and all that his life included.” And in the end, he records a kind of moral victory, as passengers throughout his subway car give up their seats, inexplicably, for a “strange-looking,” package-laden group of black and Hispanic parents and their children: “In silent agreement of a sort … the crowd … expressed a social opinion.… It was the oddest, damnedest, most piercing event.”

Alas, Brodkey is not always this good. When he is bad, he is very, very bad, and he is very, very bad quite often. Sea Battles is filled with whoppers: misstatements, overstatements, nonstatements and statements that are silly, false or incomprehensible. What does it mean, for instance, to claim that Norman Mailer, Richard Avedon, John Berryman, Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns and Paul Taylor “worked counter to modernism”? Or that Marlon Brando lacked “class bias, class identity”? (Coming soon: Stanley Kowalski and Terry Malloy played as upper-class twits.) How can one describe fearfully neurotic, and neurotically fearful, Marilyn Monroe as “Miss Unafraid … a free woman”? What does it mean to call Nazism “a bluff”? How in the world can Brodkey know that “in actuality, most people”–we assume the pulsating author excludes himself–”find sex elusive and mostly dull”?

The answer, of course, is that he can’t and doesn’t. What’s infuriating about such claims–and Brodkey’s essays are littered with them–is not just their vagueness, their pomposity, or even their stupidity. Worst of all is the absence of any supporting arguments–a key, I believe, to Brodkey’s essential contempt for his readers. Ideas are thrown out like hand grenades lobbed from a safe distance. Though Brodkey titles one essay “Reading, the Most Dangerous Game,” he seems to envision his readers as a group of extraordinarily docile players. And though his style is brawny, it is not really brave; there is a hollow core at its center, an aversion to engagement.

His scattershot approach reaches its nadir in the remarkably unprophetic, singularly unconvincing “Notes on American Fascism.” Brodkey wrote this piece in 1992, and he was responding to a real event: the polarization of wealth that resulted from 12 years of Reaganomics. But Brodkey doesn’t know what to do with this phenomenon (though writers as disparate as Joan Didion, Barbara Ehrenreich, Susan Sheehan, and William Finnegan have known) except to be very afraid. Despite Brodkey’s rather obvious lack of reportorial research, he confidently predicts that a fascist movement, or coup, or something, is “a near probability.”

Innocence Harold Brodkey

Brodkey does recognize one central truth about fascism: “[B]y preventing analysis and argument … experience itself seems to be controlled or mastered.” But he does not understand that fascism is a specific, 20th-century development. (His major historical reference point is Byzantium.) He does not understand that hating someone–like, say, Ronald Reagan–does not make you a fascist. (Fascists are bad people, but not all bad people are fascists.) He does not understand that there is still an honest-to-goodness working class right here in the U.S.A. He believes that the radical movements of the 1960’s were inspired by the “worldwide media success of Henry Kissinger.” One could go on, but why? This is the looniest, laziest political essay I’ve ever read–so loony and lazy that I initially suspected it was a satire. Brodkey ended This Wild Darkness , his valedictory memoir, aching for “glimpses of the real.” He denies us those glimpses here.

Politics weren’t really Brodkey’s turf, though. But movies were, which makes “The Kaelification of Movie Reviewing” a less understandable, and less forgivable, essay. Pauline Kael is a complex thinker, but she is also a startlingly forthright one. She’s easy to understand: Just read her. Apparently, Brodkey didn’t. He gives us the Cliffs Notes version, painting Ms. Kael as a trash-loving, demagogic barbarian. As a result of Ms. Kael’s influence, Brodkey charges, “Ideas [in movies] disappeared.… The limited subject matter and inarticulate intelligence and nearly lunatic and often infantile opinionatedness of contemporary movies is the result.”

Even a stopped clock is right twice a day. It’s true that Ms. Kael championed films she found exciting (some of which were unprecedentedly violent) and that she hated those she considered sanctimonious. She was a populist, but she never pandered to the moviegoing audience, and loathed directors who did. In fact, as the optimistic 60’s merged into the far grimmer 70’s, it was Ms. Kael who repeatedly condemned “totally nihilistic,” albeit popular, films like Clint Eastwood’s Magnum Force , and she who bemoaned the “irrational and horrifyingly brutal” entertainments that audiences increasingly sought. If today’s viewers have crummy taste, it’s hard to see why the fault is Ms. Kael’s.

But then we come upon “Jane Austen vs. Henry James,” and all–well, much–is forgiven. Brodkey shows himself to be as capacious and connected to his subject in this essay as he has been constricted and solipsistic before. He rescues Austen from safe prettiness and restores her, “shrewd and clear-eyed,” to a dangerous, imaginative place. Austen created a new–a better, broader, freer, truer –way of inhabiting the world; it was she who made Flaubert, Dickinson, Tolstoy and Whitman possible. Austen’s expansive “literary space,” Brodkey argues, is “the first great democratic use of consciousness.”

Again and again, Brodkey returns to Austen’s phenomenal truthfulness, her courageous adherence to reality, and her consequent, delightful ability to imbue language with meanings it had never previously possessed. “This is a strange, rare talent,” Brodkey wisely observes. “Words do not automatically represent things and do not automatically suggest human presence.” If only he had taken this lesson to heart; if only he had learned the import of his insight; if only he had stayed grounded like Jane Austen, a writer so earthbound she knew how to soar.